Illusion vs reality

Prem Panicker

He is Kunhikuttan. A bastard. An offspring of an illicit relationship between a low-caste woman and a leading Namboodiri (Brahmin) community leader.

He is Kunhikuttan. A bastard. An offspring of an illicit relationship between a low-caste woman and a leading Namboodiri (Brahmin) community leader.

As an adult human being, he is a facade -- trapped in loveless marriage to a woman who he does not understand and who does not understand him, and propped up by the crutch of alchohol.

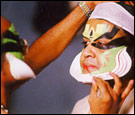

It is as a Kathakali performer that he comes into his own. When he dons the mask and the makeup, when the lights dim and the beat of the chenda (drum) swamps his senses, he leaves behind his own uncertainties, his insecurities, his deficiencies. And, in the persona of the heroes of myth and mythology, he comes alive.

She is Subhadra. Even in the woman-centric matrilineal high society of Kerala, a misfit. She is highly educated, hugely intelligent, intensely imaginative. And, at a very primeval level, passionate. And these traits are the bars of a prison that separate her from her peers, that lock her deep within the confines of her own self.

Within that prison, she explores in her mind the fantasies that thrill her, the heroes that move her, the epic stories that for her are more real than her own reality.

Of all those stories, those heroes, none is more real than Arjuna. Her grandmother conferred on her the name -- Subhadra -- of the beloved of the legendary Pandava. As a child, she was told stories of the exploits of the hero.

As a budding woman, she sees in Arjuna the epitome of all that is manly, heroic, glorious. And as Arjuna grows ever larger in her consciousness, the dividing lines between the real and the fantastic, between what is and what she believes should be, blur.

As a budding woman, she sees in Arjuna the epitome of all that is manly, heroic, glorious. And as Arjuna grows ever larger in her consciousness, the dividing lines between the real and the fantastic, between what is and what she believes should be, blur.

It is when his Kathakali troupe arrives for a private performance in one of the great ancestral tharavads (ancestral home) of Kerala that Subhadra sees, for the first time, the hero of her dreams in the flesh.

As Arjuna, Kunhikuttan is incandescent -- and Subhadra is entranced.

In the flickering flames of the oil lamps, with her senses seduced by the lilting lyrics and the pulsing throb of the chenda, Subhadra finally crosses the line from reality to fantasy, and projects her womanly dreams and aspirations onto the masked figure who holds centrestage.

For her, Kunhikuttan is Arjuna. Her destiny.

For him, coming fresh off yet another nerve-wracking verbal tussle with an unloving wife, Subhadra is a woman, beautiful and intelligent. Who -- or so he thinks -- sees, understands and appreciates the man he really is beneath the mask.

Each, for various reasons, falls in love with the other.

Each, for various reasons, falls in love with the other.

He gives her the supreme gift -- her Arjuna, the one she has conceptualised as the distillation of all that is manly in a Kathakali play of her own creation, come alive in a brilliant performance on-stage.

She gives him herself.

Dawn breaks -- and with it, the illusion. Subhadra has what she has dreamt for a lifetime -- a union with the hero of her heart and, hopefully, the seeds of pregnancy.

And he, Kunhikuttan, has nothing.

The mask is off, and daylight reveals the pitted, pock-marked visage of a flawed, insecure human being. His agony is complete when Subhadra refuses to let him see the son he has fathered.

For her, the thin divide between reality and fantasy has been successfully obliterated. She is Subhadra, sister of Krishna. Her paramour is Arjuna, the embodiment of Man. And the child growing in her womb is Abhimanyu, distillation of his father's heroic essence. Reality cannot be allowed to intrude, to mar, that fantasy.

For him, meanwhile, life has come full circle -- having started out as a son without a father, he is now a father without a son.

Never again, he vows. And Kunhikuttan sheds his heroic roles, focusing thereafter on the demonaic. Until finally, a drama that begins onstage finds its logical denouement in one last, climactic performance.

This is the story Shaji N Karun tells, rivettingly, in Vaanaprastham.

|

About Shaji N Karun

|

|

|

• Shaji Neelakantan Karun was born on January 1, 1950 in Kerala's Kollam district.

• Father N Karunakaran and mother Chandramati moved to the state capital Thiruvananthapuram in 1963 and it was here that Shaji took a bachelors' degree from University College.

• He then joined the Film and Television Institute of India, emerging with a diploma in cinematography and a president's medal for excellence.

• In 1976, Shaji was appointed as film officer in the state Film Development Corporation -- a body he now heads as its president. Around this time, he teamed up with the famed Malayalam auteur G Aravindan, and the two formed a creative partnership that redefined the way films were made in the state.

• Shaji crossed over into direction in 1988 and his first feature film, Piravi, was a stunning critical success on the Cannes marquee and elsewhere. Equally, the film made waves in theatres across Kerala, proving a point that 'art' cinema need not necessarily be out of reach of the masses.

• Shaji followed Piravi up with Swaham (1994) and again, struck it rich at Cannes where he was, by then, being feted as a director extraordinaire.

• With Vaanaprastham, which he describes as a "visual love story", Shaji has completed a hat-trick at Cannes.

• Earlier this year, Shaji resigned his post as head of the state film academy, arguing that he could not even do 50 per cent of what he had set out to do when he took up the top post.

• "And during this time, three years of my life as a filmmaker has been lost," Shaji said. "I am sad because I couldn't get support from the other members of the Academy. I took up this job to create an audience for Malayalam films internationally and for fulfilling a social commitment.

"Instead, I found myself targetted for character assasination in the media. I decided to give up the job, and concentrate on making my films."

• Up next is his second Indo-French production in a row. Kadal, based on a novel by T Padmanabhan, will be co-produced by Phillip Avriel and Sukhwant Daddha (director of Ek Chaddar Maili Si).

The film features Mohanlal in the cast, with Jaya Bachachan playing the female lead. In fact, it is Bachchan who is the protagonist of a film that will portray the life of a woman over three decades.

• Married -- again, on New Year's Day (1975) to neighbour and childhood friend Anasuya Warrier -- the Karuns have two children, Anil and Appu.

|

|

The director uses peripheral characters -- the Namboodiri who will not acknowledge his son but who secretly prides himself on his offspring's artistic prowess; the ailing Kathakali master who relives his glory through the talented disciple; the cancer-stricken vocalist; the chenda player who is Kunhikuttan's ally in alcohol; the shrewish wife; the daughter who fights to follow her father's artistic path even at the risk of her mother's displeasure -- to strike emotional sparks off the main story.

The director uses peripheral characters -- the Namboodiri who will not acknowledge his son but who secretly prides himself on his offspring's artistic prowess; the ailing Kathakali master who relives his glory through the talented disciple; the cancer-stricken vocalist; the chenda player who is Kunhikuttan's ally in alcohol; the shrewish wife; the daughter who fights to follow her father's artistic path even at the risk of her mother's displeasure -- to strike emotional sparks off the main story.

Mohanlal is incandescent as the protagonist, switching effortlessly between the tortured human being that he is, and the superhuman characters he portrays. The role demands the finished skills of an actor in his prime, and the incredible stamina that Kathakali performers acquire over a lifetime.

Suhasini Mani Ratnam, in a sense, has an even more challenging role -- in the interests of the film, she has to underplay a strongly etched character, yet use the power intrinsic to it to lift the male protagonist to an even higher plane. A delicate balancing act, which Suhasini manages with aplomb.

The peripheral characters are drawn from the pick of the Kalamandalam talent -- their mastery of Kathakali has been proven in temples and stages across the land. But here, they show talent of a different kind, turning in restrained, compelling performances in their various roles.

Two master technicians play integral roles in the crafting of Vaanaprastham. One is Zakir Hussain, the tabla maestro who creates the lyrical background score. Kathakali is a percussion-driven art form, and Hussain is a master who, with this score, gives the film its throbbing heartbeat.

The other is Renato Berta, the French cinematographer who has worked with the likes of John Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and Alain Resnais. Creatively, what he has to do in Vaanaprastham is an artistic progression on what he did, earlier, in Daniel Schmids' Kabuki-inspired The Written Face.

The other is Renato Berta, the French cinematographer who has worked with the likes of John Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and Alain Resnais. Creatively, what he has to do in Vaanaprastham is an artistic progression on what he did, earlier, in Daniel Schmids' Kabuki-inspired The Written Face.

Visually, Berta takes the rich architecture of the century-old Thirumullapalli Temple (in Karalmanna village, Palakkad district) and the verdant landscape of Kerala to produce a lush, richly-textured visual examination of the relationship between myth and reality.

From a viewer's point of view, it is interesting that after watching the film, you come away talking of the passionate 'virtual love story', of the stunning visuals, of Mohanlal's brilliance and Suhasini's surcharged performance -- but rarely, if ever, of the director.

Perhaps that is Shaji N Karun's biggest victory. He is there, in the meticulously etched story and the sparse, telling dialogues. He is there in the use of Kathakali as a medium -- inspired, perhaps, by his mentor, the late Malayalam auteur Aravindan's 1988 opus, Marattam.

He is there in the inch-perfect meshing of story and song and dialogue and performance into a celluloid classic. And yet, he is never there, his contribution is never overt, his hand on the wheel is gossamer-light.

The film is co-produced by Mohanlal under his Pranavam Arts International banner and Pierre Assouline of Euro-American Films at an estimated budget of $ 1 million.

Also Read:

'I have no roots'

'Life itself is a daily celebration'

Payback time!