|

|

| Help | |

| You are here: Rediff Home » India » Business » Columnists » Guest Column » Manohar Mason |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The perils of developing a social science are perhaps best captured in the fault lines between theory and practice. Grand theories, broad in sweep and scope, often come a cropper when applied to complex, real life situations.

The perils of developing a social science are perhaps best captured in the fault lines between theory and practice. Grand theories, broad in sweep and scope, often come a cropper when applied to complex, real life situations.

Or, seemingly timeless insights turn out to be just transient truths. At best, they work in the particularities of a given situation and collapse like the proverbial deck of cards when external circumstances change.

It is to Peter Drucker's (1909-2005) enduring credit that he made management into, as he famously put it, a practice -- a set of purposeful tasks that can be organised, much like medicine or engineering. The father of modern management transformed it into a specific and systematic work based on an organised body of knowledge that is both teachable and learnable, rather than treating it as something esoteric and mysterious.

Drucker's insights can be of tremendous help to any management practitioner. But, they often ran contrary to what common sense advocated. Here's Drucker on some vital management beliefs, contrasted with conventional wisdom on the same issue.

Conventional wisdom (CW) : Executives need to develop the ability to make many decisions rapidly and accurately.

Peter Drucker (PD): The effective decision-maker actually makes very few decisions. This is because he recognises that most problems he faces are generic. They are not unique, one-off events. He, therefore, establishes a rule, a principle or a policy to handle all such situations.

He always assumes that the event that clamours for his attention is in reality a symptom. He looks for the true problem. He is not content with just doctoring the symptom.

He then makes a decision on principle at the highest possible conceptual level. This does not, as a rule, take longer than a decision on symptoms or expediency. Because the manager solves generic situations through a rule and policy, he can handle most events as cases under the rule; that is, by adaptation. This is why he does not need to make many decisions.

For instance, when Alfred Sloan, Jr, took over General Motors in 1922, he was faced with a company struggling for survival with about half a dozen divisions each headed by capable but almost independent chieftains, all pulling in different directions.

Everyone before Sloan had seen the problem as one of personalities, to be solved through a struggle for power, from which one man would emerge victorious. Sloan saw it as a constitutional problem to be solved through a new structure, that is, decentralisation, which balances local autonomy in operations with central control of direction and policy.

Sloan thus identified the generic problem, which was one of organisational structure, and solved it at the highest conceptual level through decentralisation.

CW: It is important for an executive to plan his work.

PD: As Drucker put it, the above advice sounds eminently plausible. The only trouble with it is that it rarely works. The plans always remain on paper, as good intentions.

Effective executives, as Drucker observed, do not start with their tasks. They start with their time. And they do not start out with planning their time. They start by finding out where their time already goes (by recording how it is actually spent by keeping a time log).

Then they attempt to manage their time and to cut back unproductive demands on their time. Finally, they consolidate their "discretionary" time into the largest possible continuing units. This three-step process -- of recording time, managing time and consolidating time -- is the foundation of executive effectiveness.

CW: When making staffing decisions, a manager must be alert to the weaknesses of a prospective candidate.

PD: The effective executive fills positions and promotes on the basis of what a man can do. He does not make staffing decisions to minimise weaknesses but to maximise strengths. This is because to try to build against weakness frustrates the purpose of organisation. Organisation is a specific instrument to make human strengths redound to performance while human weakness is neutralised and largely rendered harmless.

Drucker quoted the following example to illustrate his point. Abraham Lincoln, when told that General Ulysses S Grant, his new commander-in-chief, was fond of the bottle, said: "If I knew his brand, I'd send a barrel or so to some other generals." After a childhood on the Kentucky and Illinois frontier, Lincoln assuredly knew all about the bottle and its dangers.

But of all the Union generals, Grant alone had proven consistently capable of planning and leading winning campaigns. Grant's appointment was the turning point of the Civil War. It was effective because Lincoln chose his general for his tested ability to win battles, and not for his sobriety, that is, for the absence of a weakness.

CW: Executives need to be good problem-solvers.

PD: While problem-solving is an important task, one must always keep in mind that an organisation obtains results by exploiting opportunities, and not by solving problems.

All one can hope to get by solving a problem is to restore normality. At best, it can help eliminate a restriction on the capacity of the business to obtain results. The results themselves must come from the exploitation of opportunities.

CW: Entrepreneurs are a breed apart from other people with a different psychology and character traits.

PD: Entrepreneurship is not about character traits. It is not something mysterious -- whether a gift, talent, inspiration, or "flash of genius". Entrepreneurship is a purposeful task that can be organised. It is a question of behaviour, policies and practices rather than personality. It is a discipline that can be learned.

What's more, entrepreneurship is part of every executive's job and needs to be mastered by any manager who wishes to be effective.

These are just glimpses of what one can learn from Drucker. No wonder, as eminent a practitioner of management as Andrew Grove, co-founder of Intel, remarked of Drucker, "He spoke in plain language that resonated with ordinary managers. Consequently, simple statements from him have influenced untold numbers of daily actions; they did mine over decades."

Unfortunately, even today, management still tends to get carried away by style rather than substance, by the fad of the day rather than a deeper understanding of issues and by what I would term "fragmentary" thinking -- which focuses only on a part of the picture -- rather than looking at things as a whole.

Drucker was the exact antithesis of all these tendencies. He brought depth and maturity in thinking to every issue he addressed. He was ahead of his time on most issues and always focused on major trends rather than getting carried away by the blips on the radar screen. Most important, he was the first to look at management as a whole rather than just one aspect of it and to build it on a firm foundation for future generations.

Drucker invented management and was its most eminent torch bearer for close to 60 years. With his passing last November, the world has lost one of its finest thinkers. The millions of Drucker fans around the globe have lost a "once-in-a-lifetime" teacher.

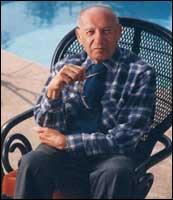

Peter F Drucker (1909-2005) |

Manohar Mason is Managing Director of Pentagon Communications.

Do you want to discuss stock tips? Do you know a hot one? Join the Stock Market Discussion Group.

Powered by

More Guest Columns

|

|

| © 2008 Rediff.com India Limited. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer | Feedback |