Home > Cricket > World Cup 2003 > Columns > Prem Panicker

Left arm over -- and out

March 21, 2003

Images are visceral, they tell a story far better than words can.

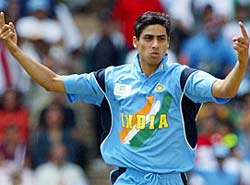

The story of Ashish Nehra, thus, is ideally told through images; snapshot chronicles of a sportsman who awoke one morning to find himself the repository of a nation's hopes and cricketing aspirations.

Image Number 1: Ashish Nehra, coming in as first change, to Zimbabwe's master batsman Andy Flower. A delivery from wide of the crease, angling in on length to the left-hander, hitting the deck, drawing the batsman forward, hurrying away again as if it had an appointment with the edge of the bat -- which it just misses. Flower blinks in surprise. The giant scoreboard confirms why: the delivery has clocked 149.2 on the speed gun, and that is seriously fast.

Image Number 2: Ashish Nehra is given the new ball against Namibia -- recognition of, and reward for, his stunningly sudden move up the ranks of the fast men. He runs in to bowl the second ball of his first over, and his right leg seems to go out from under him. He comes crashing down, then limps off the ground, never to return.

"One day you are a hero," said baseball legend Babe Ruth, "and the next day a bum." Nehra's plight was worse -- one day he was a newly written check, an unfulfilled promise; the next day, the check bounced.

Image Number 3: The crucial game against England is at the halfway stage. The Indians run out onto the park, prepared to defend its score of 250. Nehra -- the state of whose ankle has, over the preceding days occasioned more debate than the national budget -- is part of the pack. And in the dressing room, a forlorn expression on the face he cups in a hand more used to cupping a cricket ball, sits Anil Kumble, the veteran leg-spinner whose best chance of playing a Cup game lay in Nehra's sitting out.

The rest is history. Nehra comes on to bowl in the 13th over. His second ball is caressed by Michael Vaughan for four. His third escapes being called a wide. Fellow seamer Zaheer Khan and skipper Sourav Ganguly wet-nurse the bowler, meeting him mid-pitch as soon as he completes his follow through, patting him on the back, exhorting him, and walking with him back to his mark.

His next over, the 15th, is better -- the line straightens, the ball begins to move in the air and off the deck, the rhythm is coming back.

The 17th over begins -- and Nehra hits his straps. He swings, he seams, he lands on length with the inevitability of a bowling machine. The second ball (what is it with Nehra and second balls?) is a scorcher, on length, angling across the right-handed Nasser Hussain, finding the edge for Rahul Dravid to hold. A ball later, Alec Stewart follows him -- trapped in front, first ball, by another superb delivery.

Nehra has a celebratory style all his own -- a kangaroo leap in the air, then a swooping, airplaning run across the field with arms spread wide, like a plane at take off. On the day, he "takes off" so often, you would think Kingsmead, Durban, was LA International Airport.

The cameras, meanwhile, flash to the team's dressing room -- where the plethora of managers this team is blessed wore smiles wider, if that is possible, than the successful bowler's.

Only one man sits pensive: Anil Kumble, torn between rejoicing over his mate's performance on the field, and the excruciating fear that he could have played his last Cup game.

That is how sport is -- one gets to rewrite his own destiny and, in doing so, he erases another's. Even as you create your own myth, you shatter that of a comrade, a colleague, a mate -- and therein lies the beauty, and heartless cruelty, of sport at the highest level.

**************

Just who is Ashish Nehra? And from where did it all come, this skill, this pace, this determination, this physical strength that allowed him, three days after limping off the field, to bowl 10 overs at a stretch at speeds not previously touched by an Indian?

He debuted against Zimbabwe at the Harare Sports Club ground -- and took out star batsman Alistair Campbell caught behind in the second ball (that motif, again) of his international career.

He debuted against Zimbabwe at the Harare Sports Club ground -- and took out star batsman Alistair Campbell caught behind in the second ball (that motif, again) of his international career.

His inclusion was symptomatic of, and part of, a paradigm shift in India's cricketing mindset. The country that once used Sunil Gavaskar to take the shine off the ball before tossing it to its assembly line of world-class spinners was now looking, after 16 years of winning at home and being drubbed abroad, to pace to provide parity with the rest of the world.

It was a good time to be a seamer, and anyone with a run-up of more than 6 yards seemingly qualified for that label.

India already had a few -- Javagal Srinath the pater familias, who rested as often as he played; Ajit Agarkar the prodigal who, far too often, lived outside the means his ability afforded; Zaheer Khan the brash, aggressive, in-your-face quick gradually taking over the lead bowler's slot...

And tagging along, to provide backup as needed, was this gangly young man, all legs and outsize arms, with a vacuous expression and a naïve good humor.

On the plus side, he could move the ball off the seam either way and, when he wanted to, use height and straight high arm to make the ball lift off length. On the minus side, his weird delivery stride was a surefire groin-buster -- toe of leading leg pointing at the batsman, toe of back leg pointing in the exact opposite direction, to the sightscreen behind his back.

Sure enough, the groin gave out; sure enough, when he returned with a re-tooled bowling action, his standards dropped. He found himself now out of the side, now in -- his returns more due to the fact that there didn't seem much left in the cupboard.

In 14 matches out of 32 before the India-England clash, he went wicket-less; in another 6, he took a solitary wicket to "justify" his inclusion, for a total haul of 30 wickets in 32 matches.

This was what we could see -- his performance on the field. And it caused us to ask, why Nehra? Why not Kumble? Or Agarkar? Or anyone at all?

Off it, though, and away from the eyes of the media and the fans, much was happening that does not reflect in the spreadsheets of statisticians.

In 2002, India acquired a young, professional physical trainer from South Africa. Adrian Le Roux had no use for the prevalent theory that Indians could not become good athletes, powerful fast bowlers -- after spending a month or two sussing out the team, he pushed them over the edge of previously charted comfort zone, and into a punishing new world of focused workouts and rigorously monitored diets.

Rice and heavily fried chicken was history; protein-centric diets and Myoplex shakes became the norm. The players, Nehra among them, lost that comfortable cushioning of fat, their cheeks became sunken, their mommies took to telephoning the trainer in anguish.

But they also became stronger, fitter as they -- initially skeptical, but increasingly with the fanaticism of new-minted converts -- adopted the grueling regimen. Powerful muscles defined themselves as the camouflage of fat was shed -- and suddenly, everything seemed possible.

The team's mindset, too, began to change. Speaking of his own seniors, Javagal Srinath once remarked that they had taught him nothing, failed to share their experiences, their learnings; that he had to invent the wheel all over again.

That frustration translated into a readiness, on the part of the senior bowler, to take the younger ones under his wing, to work with them on the composite parts of the fast bowler's craft.

The youngsters, Zaheer and Nehra, were quick to respond: rivals, in a sense, for the same slot, they pumped each other up, monitored each other's practice sessions, traded secrets and techniques, and grew in tandem.

Nehra did not find a place in the starting line-up for India's World Cup lung-opener against The Netherlands. He was left out of the game against Australia. His inclusion in the side to play Zimbabwe owed much to the seam-friendly conditions on offer at the Harare Sports Club, where he had made his debut two years earlier.

His spell there was quick enough to raise eyebrows -- and with 0/35 to show for seven overs, unimpressive enough to provoke the why-is-he-here? questions all over again. Tripping and falling in the first over of the next game didn't help much either.

And yet, for the key game against England, it was his fitness that the team worried about the most -- after all, the think tank of Sourav, Rahul, Sachin and Wright were the ones who knew best just how much progress he had made.

We will never know what it was like, for Nehra, as he stood at the top of his bowling mark on the 26th of February. Apprehension? Extreme concern for his extremities -- given that he already had one ankle operated on, and the other one had given way under him the last time he played?

Fear of failure, possibly?

This is what sport is about, at its core. It is fascinating to watch someone confront fear, live through it, respond to it in visceral fashion.

Fear inspires some; others, it destroys.

On that day, it inspired Nehra to bowl in a dervish-trance of near-perfection. Figures of 6-2-23-6 tell the story of a bowler who rose beyond the occasion; who raised the bar and roused the hopes of a nation that has long suffered, albeit vicariously, under the hammer of fast bowlers from other lands and hoped to give back as good as it got.

Flash in the pan, the muted whisper went, as Nehra went for 2/74 in 10 overs against Pakistan in his next outing; a zero in the wickets column against Kenya in the outing after that made the whispers gain momentum.

'That England game, it was under lights after all; look at that chap James Anderson, bowled so well under lights against Pakistan, couldn't come near it ever since.'

A horse for one particular course? Fear of success, more debilitating at times than fear of failure?

Only Nehra and his bowling mates, Srinath and Zaheer, knew. And, as they have done throughout this campaign, they continued their work, in tandem, in the nets.

The answer was given not through press conferences, but on the field of play. 7-1-35-4 against Sri Lanka; 10-3-24-1 versus New Zealand; 5-1-11-2 versus Kenya.

Nehra had arrived -- and he brought with him an answer to a key puzzle. Typically, India had managed to bowl well in the first ten overs, only to give the game away with the first bowling change.

Now, the team had an attacking bowler coming in at number three -- which meant that opponents who figured on seeing off Srinath and Zaheer without too much damage found themselves confronting a bowler equally aggressive, only faster.

"We had concentrated on (India's) batting," Australian captain Ricky Ponting was moved to say, Friday. "It's time to start thinking about their bowling."

On Sunday, when Sourav Ganguly tosses him the ball and Nehra runs in to bowl to the Australian middle order, it will be both supreme test, and validation, in one.

{An earlier version of this article first appeared in the issue of India Abroad dated March 7, 2003)

More Columns